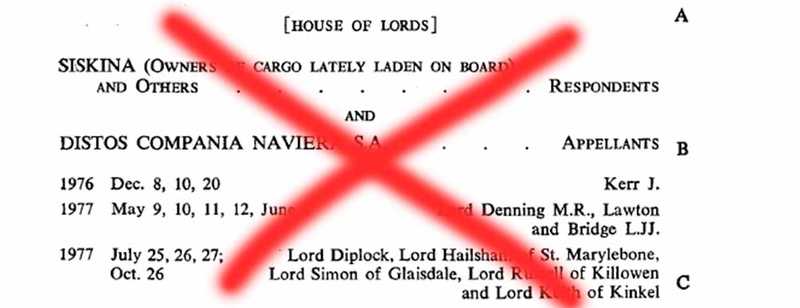

1. Siskina: more holes than a seive

Lord Diplock’s reasoning in The Siskina is unconvincing. This can be shown in two ways.

First, because the House of Lords had to qualify it substantially in South Carolina Insurance Co [1987] AC 24.

There, the single test laid down by the Siskina for the grant of an injunction (essentially: does the injunction directly support a cause of action justiciable in the jurisdiction) morphed into a two-pronged test with two exceptions.

More specifically, Lord Brandon explained that an injunction could be granted

- where the respondent had invaded, or threatened to invade, a legal or equitable right of the applicant (provided the court has jurisdiction to enforce that right); or

- where the respondent had behaved, or threatened to behave, in an unconscionable manner; or

- (exception 1) to restrain foreign proceedings on forum non conveniens grounds; or

- (exception 2) to grant a freezing order.

Secondly, because there are still a number of injunctions routinely granted by the courts that do not fall within even the expanded South Carolina list.

Those highlighted by the judgment of the majority of the seven-member board of the Privy Council (Lord Leggatt, with whom Lords Briggs, Sales and Hamblen agreed) were:

- Norwich Pharmacal and Bankers Trust disclosure orders (i.e. orders made against innocent third parties to help a claimant to bring a claim or identify the traceable proceeds of misappropriated assets) (see [48]-[49]).

- Website blocking orders (i.e. orders made against internet service providers requiring them to block websites selling counterfeit goods) (see [50]-[51]).

- Orders granted to prevent the court’s process from being abused (e.g. injunctions restraining the presentation of a winding-up petition) (see [54]).

2. So what are the limits on the court’s jurisdiction to grant an injunction?

The short answer to this question is: there are none.

The slightly longer answer is found in Lord Leggatt’s approval of the following passage from Spry’s Equitable Remedies (at [57]):

“The powers of courts with equitable jurisdiction to grant injunctions are, subject to any relevant statutory restrictions, unlimited. Injunctions are granted only when to do so accords with equitable principles, but this restriction involves, not a defect of powers, but an adoption of doctrines and practices that change in their application from time to time. Unfortunately there have sometimes been made observations by judges that tend to confuse questions of jurisdiction or of powers with questions of discretions or of practice. The preferable analysis involves a recognition of the great width of equitable powers, an historical appraisal of the categories of injunctions that have been established and an acceptance that pursuant to general equitable principles injunctions may issue in new categories when this course appears appropriate.”

3. How does all this affect the grant of WFOs?

At a jurisprudential level, Lord Leggatt explained at [83] that:

“... at this stage of the law’s development it is possible to go further and recognise that a freezing injunction is not, on a true analysis, ancillary to a cause of action, in the sense of a claim for substantive relief, at all”.

Instead, a freezing order is best rationalised on the basis that its essential purpose is

“to facilitate the enforcement of a judgment or order for the payment of a sum of money by preventing assets against which such a judgment could potentially be enforced from being dealt with in such a way that insufficient assets are available to meet the judgment.” (at [85])

This focus on enforcement provides a proper foundation for the established practice of freezing the assets of non-cause of action defendants (NCADs) – for example where an NCAD holds assets on bare trust for a fraudster.

And in practice?

On a practical level, the Privy Council confirmed that the practice of refusing freezing relief before a right to payment of a debt or damages has accrued (eg because a loan has not yet fallen due) should no longer be followed. In other words, the decision of the Court of Appeal in The Veracruz I [1992] 1 Lloyd’s Rep 353 can be consigned to the dustbin.

4. Summary of current practice

The majority’s judgment included the following executive summary at [101]-[102]:

“[101] In summary, a court with equitable and/or statutory jurisdiction to grant injunctions where it is just and convenient to do so has power - and it accords with principle and good practice - to grant a freezing injunction against a party (the respondent) over whom the court has personal jurisdiction provided that:

i) the applicant has already been granted or has a good arguable case for being granted a judgment or order for the payment of a sum of money that is or will be enforceable through the process of the court; ii) the respondent holds assets ... against which such a judgment could be enforced; and iii) there is a real risk that, unless the injunction is granted, the respondent will deal with such assets (or take steps which make them less valuable) other than in the ordinary course of business with the result that the availability or value of the assets is impaired and the judgment is left unsatisfied.

[102] Although other factors are potentially relevant to the exercise of the discretion whether to grant a freezing injunction, there are no other relevant restrictions on the availability in principle of the remedy. In particular:

i) There is no requirement that the judgment should be a judgment of the domestic court - the principle applies equally to a foreign judgment or other award capable of enforcement in the same way as a judgment of the domestic court using the court’s enforcement powers. ii) Although it is the usual situation, there is no requirement that the judgment should be a judgment against the respondent. iii) There is no requirement that proceedings in which the judgment is sought should yet have been commenced nor that a right to bring such proceedings should yet have arisen: it is enough that the court can be satisfied with a sufficient degree of certainty that a right to bring proceedings will arise and that proceedings will be brought (whether in the domestic court or before another court or tribunal).”

5. The minority and the future

The minority (Sir Geoffrey Vos and Lords Reed and Hodge) agreed with the result but did not think that the Privy Council should seize the opportunity to overrule the House of Lord’s reasoning in The Siskina.

As someone who has had to work very hard to get around The Veracruz, I am pleased that the majority grasped the nettle: we now have a coherent statement of principle, and the tantalising possibility of seeking injunctions in entirely new contexts.